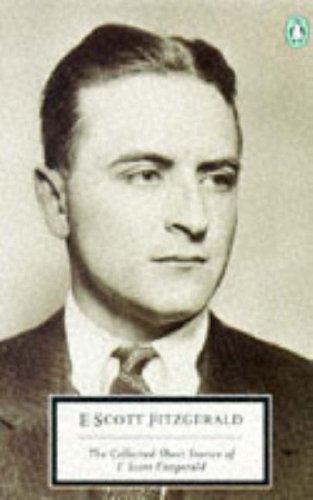

A while back I posted about the less-than-busy doctors of Victorian detective fiction. Another medical archetype of fiction is the irritatingly bluff doctor. While Dr Gregory in F Scott Fitzgerald’s short story “Gretchen’s Forty Winks” is a minor character, he encapsulates a certain cheery complacency.

This story is not among Fitzgerald’s best. An awful lot of Fitzgerald’s writing was for money, in the midst of a chaotic life. There’s nothing wrong with this – remember Dr Johnson’s dictum that no man but a blockhead writes except for money. However, “Gretchen’s Forty Winks” is no Great Gatsby. There is also much that would now be deemed sexist, not to mention casual gaslighting and slipping of Mickey Finns within the marital relationship . Of course, no doubt there is much we find unexceptional or even virtuous in our own culture which will in nearly a century seem laughably unethical.and the story has some by-the-way flashes of Fitzgerald’s acuity and brilliance. It also has some historical interest as an portrayal of what might have been seen as a “balanced life” in 1924.

The story was published in the Saturday Evening Post of March 15, 1924.

It is a rather heavy handed spoof of the cult of the “balanced life” (nowadays we would say work-life balance). The protagonist, Roger Halsey, is an advertising man, who has struck out for himself having left “the New York Lithographic Company.” We meet him coming home to his wife Gretchen. Fitzgerald writes thus of their marriage: “it was seldom that they hated each other with that violent hate of which only young couples are capable, for Roger was still acutely sensitive to her beauty.” Halsey has to work for forty solid days to obtain “some of the largest accounts in the country”, to the disappointment of his wife – “she was a Southern girl, and any question that had to do with getting ahead in the world always gave her a headache.”

His wife introduces Halsey to George Tompkins, an interior designer and devotee of the “the balanced life.” An irritated Halsey asks for a definition:

“Well’ – he hesitated – probably the best way to tell you would be to describe my own day. Would that seem horribly egotistic?”

“Oh no!” Gretchen looked at him with interest. ‘I’d love to hear about it’

‘Well, in the morning I get up and go through a series of exercises. I’ve got one room fitted up as a little gymnasium, and I punching the bag and do shadow-boxing and weight-pulling for an hour. Then after a cold bath – There’s a thing now? Do you take a daily cold bath?’

‘No,’ admitted Roger. ‘I take a hot bath in the evening three or four times a week.’

A horrified silence fell. Tompkins and Gretchen exchanged a glance as if something obscene had been said.

‘What’s the matter?’ broke out Roger, glancing from one to the other in some irritation. ‘You know I don’t take a bath every day – I haven’t got the time.’

Tompkins gave a prolonged sigh.

‘After my bath,’ he continued, drawing a merciful veil of silence over the matter, ‘I have breakfast and drive to my office in New York, where I work until four. Then I lay off, and if it’s summer I hurry out here for nine holes of golf, or if it’s winter I play squash for an hour at my club. Then a good snappy game of bridge until dinner. Dinner is liable to have something to do with business, but in a pleasant way. Perhaps I’ve just finished a house for some customer, and he wants me to be on hand for his first party to see that the lighting is soft enough and all that sort of thing. Or maybe I sit down with a good book of poetry and spend the evening alone. At any rate, I do something every night to get me out of myself.’

Roger is unimpressed. As the story progresses, he keeps to his exacting work schedule, until he nearly has secured a major account. Gretchen has chafed all along at the economising, and the night before a crucial submission forces another dinner with Tompkins. At this, Roger and Tompkins end up having a blazing row, simmering with the fury of the man who suspects he be becoming a cuckold:

“‘Are you implying my work is useless?’ demanded Tompkins incredulously.

‘No: not if it brings happiness to some poor sucker of a pants manufacturer who doesn’t known how to spend his money'”

SPOILER ALERT!

After ejecting Tompkins from his house, Roger resorts to obtaining something unmentioned from the local drugstore, and putting “into the coffee half a teaspoonful of a white substance that was not powdered sugar” before giving it to his wife. He also hides all her shoes in a bag.

This allows him to spend all night working on the account (not before giving his grumpy landlord the bag of shoes as a guarantee, having missed that month’s rent) with ultimate success. A contrite Gretchen awakes after a full day going missing from her life, thanks to her husband’s deployment of white powder, and so distressed is she at finding her shoes missing that Roger agrees to take her to the doctor. Enter Doctor Gregory, a man for whom the word ‘confidentiality’ has no meaning:

The doctor arrived in ten minutes.

‘I think I’m on the verge of a collapse,’ Gretchen told him in a strained voice.

Doctor Gregory sat does on the edge of the bed and took her wrist in his hand.

‘It seems to be in the air this morning.’

‘I got up,’ said Gretchen in an awed voice, ‘and I found that I’d lost a hole day. I had an engagement to go riding with George Tompkins -‘

‘What?’ exclaimed the doctor in surprise. Then he laughed.

‘George Tompkins won’t go riding with anyone for many days to come.’

‘Has he gone away?’ asked Gretchen curiously.

‘He’s going West.’

‘Why?’ demanded Roger. ‘Is he running away with somebody’s wife?’

‘No,’ said Doctor Gregory. ‘He’s had a nervous breakdown.’

‘What?’ they exclaimed in unison.

‘He just collapsed like an opera-hat in his cold shower.’

‘But he was always talking about his – his balanced life,’ gasped Gretchen. ‘He had it on his mind.’

‘I know,’ said the doctor. ‘He’s been babbling about it all morning. I think it’s driven him a little mad. He worked pretty hard at it, you know.’

‘At what?’ demanded Roger in bewilderment.

‘At keeping his life balanced.’ He turned to Gretchen. ‘Now all I’ll prescribe for this lady here is a good rest. If she’ll just stay around the house for a few days and take forty winks of sleep she’ll be as fit as ever. She’s been under some strain.’

Dr Gregory’s utter disregard for confidentiality is impressive in its brazenness (and if he could make a house call in ten minutes he is himself presumably impressively non-busy) but, for me, the height of his irritatingness is still to come:

‘Doctor,’ exclaimed Roger hoarsely, ‘don’t you think I’d better have a rest or something. I’ve been working pretty hard lately.’

‘You!’ Doctor Gregory laughed, slapped him violently on the back. ‘My boy, I never saw you looking better in your life.’

“slapped him violently on the back” – truly Dr Gregory is a prince among doctors… (the phrase also pops up in James Herriot)

As for the more general spoof of “the balanced life”, it is surely wise to reflect moderation in all things is wise, especially moderation. A suspicion of overly-programmed approaches to nature and leisure underlies my mild suspicion of “forest bathing” One of the founders of The Idler once wrote about having a breakdown due to his frenetic life of writing and talking about the wonders of idleness.

But it might also be wise to recall that Fitzgerald’s book of autobiographical writings was called The Crack-Up.